International Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Hyperinsulinism; what do they mean for us? A guide for young people, families and carers.

These guidelines are linked directly to the International Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Hyperinsulinism 2023. The paragraphs correspond to the original document, enabling the reader to move between the two documents as they choose. Some of the background genetic information is in italics; please ask your clinician for more information if needed.

Major topics covered include:

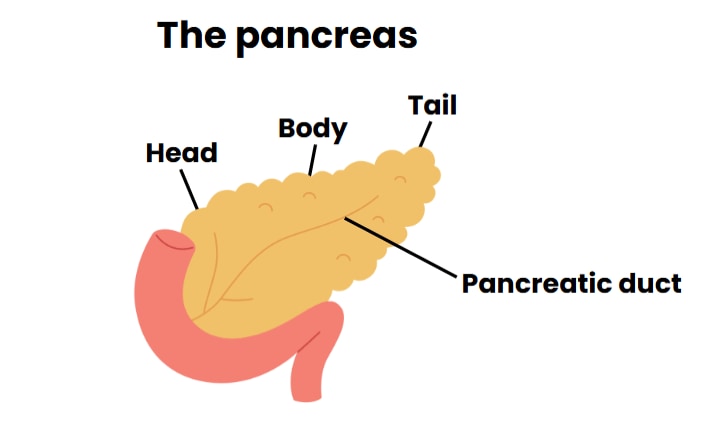

Hyperinsulinism (HI) is caused by a problem in the pancreas (the pancreas is an organ below the stomach).

Insulin is made in the pancreas and sent around the body to keep the amount of glucose in the blood at a particular level (blood sugar and blood glucose both mean the same thing). Glucose is an important fuel for the brain and the body.

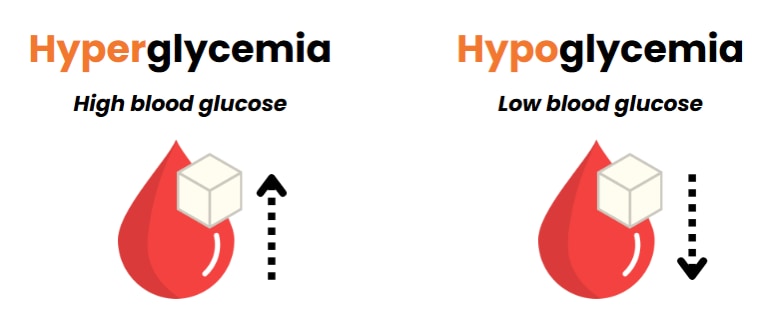

People with HI make too much insulin. Too much insulin makes blood glucose levels low (low blood glucose is also called hypoglycemia). HI is the most common and most severe cause of long-lasting hypoglycemia in babies and children.

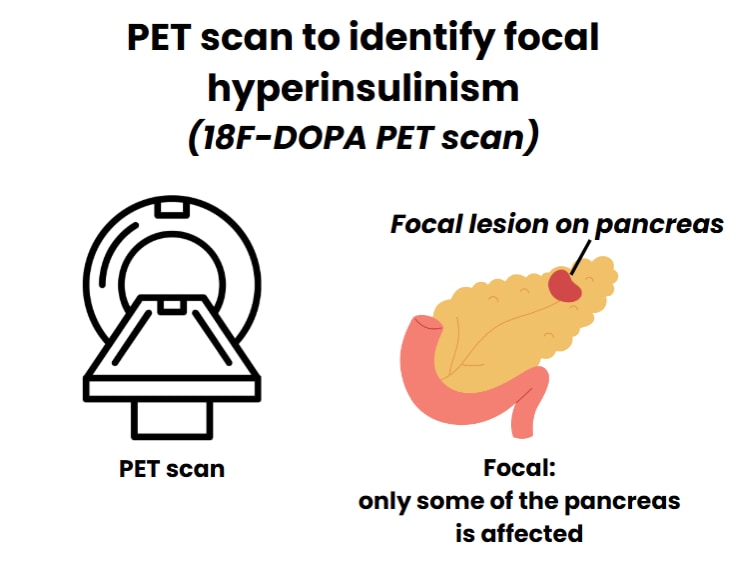

It’s been 65 years since HI was first written about in scientific medical papers. Since then, there have been a lot of improvements in how HI is diagnosed. Now we use genetic testing and a special imaging test (like an x-ray) called an 18F-DOPA PET scan (which will be referred to as PET scan) to help find focal HI (where only a small part of the pancreas is affected). However, there have been almost no new ways to treat HI since the medicine diazoxide was first used in the 1960s.

Research about newborns and genetics has helped hospital teams understand more about transient (temporary) and persistent (long-lasting) forms of HI in newborn babies.

Now, we can get genetic test results quickly, and, along with a PET scan, this can help us to find a focal lesion in the pancreas. A focal lesion can be removed by surgery, curing many children who have the focal form of HI. These tests are often only available in highly specialized hospitals in certain countries.

Diazoxide is the only FDA-approved drug for treating HI (this means the drug has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration and has gone through extensive testing that has showed it to provide a health benefit that outweighs risks). Diazoxide is considered an “essential medicine” by the World Health Organization. Diazoxide is not available in many countries. New treatments for HI are being developed, and trials looking at safety and effectiveness are being conducted.

This paper about the diagnosis and management of HI was written by HI experts from across the world to help specialists, pediatricians (children’s doctors), and neonatologists (doctors who work with newborns) to recognise and treat HI. The aim is to reduce the number of children who have a brain injury caused by hypoglycemia.

A scientific medical paper about the diagnosis and management of HI in Japan was published in 2017. This document is an updated guideline for the management of babies and children with HI and includes how management can be adapted for less-developed regions of the world where resources may be limited.

How these guidelines were developed

There were 17 specialists on the guideline writing committee, and the guidelines took 3 years to write. The committee read everything that had already been published about HI and used it to make a document with guidelines on how to treat HI. The document was read by a larger group of endocrinologists (doctors who are specialists in hormone disturbances); their comments were used to help make the final version.

1. The Diagnosis of Hyperinsulinism

1.1 We recommend making a diagnosis of hyperinsulinism based on blood tests during an episode of hypoglycemia.

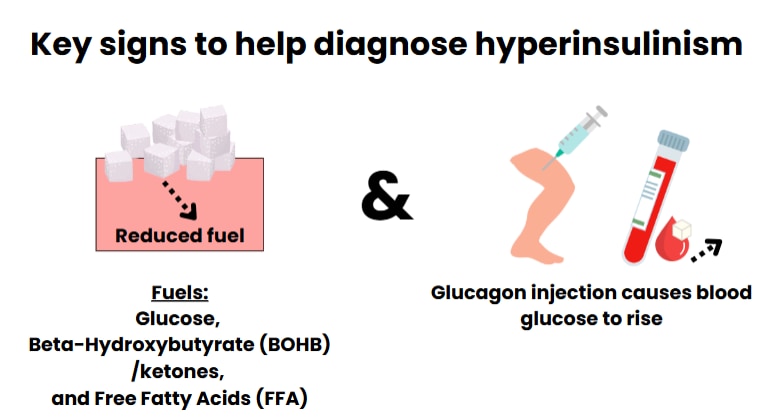

The blood tests look at levels of fuels used by the body [the fuels are beta-hydroxybutyrate (BOHB) and free fatty acids (FFA)] and levels of hormones produced by the body. The hormones are insulin, growth hormone, and cortisol. The tests also look at how the blood glucose levels respond to giving the child a dose of glucagon (glucagon is a hormone that helps to raise blood glucose levels).

The diagnosis of HI is made if the pancreas makes more insulin than expected, and/or if insulin levels are higher than expected when the individual is hypoglycemic.

Insulin levels in the blood should be measured by blood tests. If the child needs more glucose than expected to keep blood glucose in the normal range, this may be a clue that their pancreas is making too much insulin. Other blood tests will show that levels of other fuels are too low and that there is a larger than expected blood glucose response to glucagon during hypoglycemia.

Reduced levels of fuels in the blood and a large blood glucose response to glucagon are key signs of hyperinsulinism.

Glucagon is a hormone that is given as an injection. A large blood glucose response to glucagon can be used to diagnose HI, particularly when the insulin levels in the blood are low (except when there is a problem with hormones made in the pituitary gland).

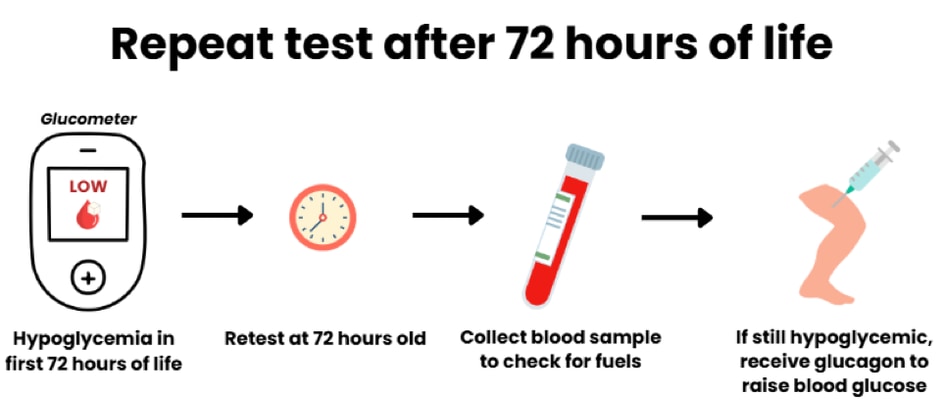

Newborn babies often have lower blood glucose levels during the first 72 hours of life. This is known as ‘transitional hypoglycemia’. If tests to diagnose HI are done before 72 hours of age, these tests should be repeated after 72 hours of age to confirm the diagnosis of HI if the child still has hypoglycemia and high insulin levels.

Tests that try to stimulate insulin production and hypoglycemia with glucose, leucine, or protein are not useful for making the diagnosis of HI but may help to determine the type of HI.

1.2 We recommend genetic testing for all children with hyperinsulinism except for children likely to have an acquired form of HI (not caused by changes to genes).

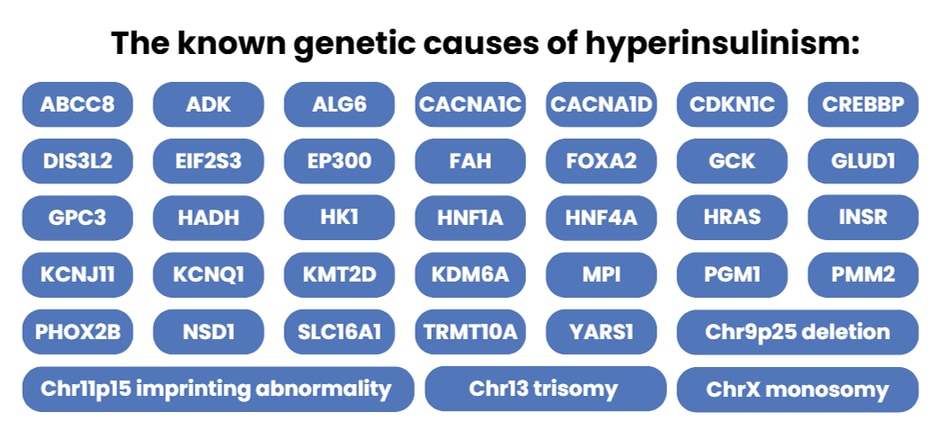

Over 30 different genetic subtypes of HI have been described.

1.3 We recommend that babies with hyperinsulinism are checked for the possibility of a syndrome which can also affect other parts of the body.

1.4 We recommend that all children with hyperinsulinism that begin to show signs after the age of 2 years are screened for insulinoma (a tumor in the pancreas that makes too much insulin).

It is important to find out the cause of HI because this may help with the choice of treatment and long-term follow-up.

Hyperinsulinism in a newborn baby can be caused by either genetic or acquired conditions.

Acquired Hyperinsulinism

Sometimes acquired HI may be due to perinatal stress (problems around the time of birth). Some examples include:

- Diabetes in the mother

- Stress to the baby around the time of birth (perinatal stress)

- Lack of oxygen to the baby during birth (birth asphyxia)

- Slow growth in the womb (intrauterine growth restriction)

- Exposure to drugs taken by the mother during pregnancy

- High rates of glucose infusions to the mother during delivery

Perinatal Stress-Induced HI (PSHI) occurs in approximately 1 in 1,200-1,700 newborns. Babies with PSHI usually have hypoglycemia in the first 24 hours of life; the hypoglycemia often gets better within the first 10-14 days of life. In approximately 1 in 12,000-13,600 newborns, a more severe form of PSHI can happen which lasts beyond the first 2 weeks of life and may require treatment with diazoxide. Genetic testing is not usually recommended for babies with PSHI because researchers have not found a genetic cause for PSHI.

When there is a family history of a type of diabetes known as Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY: a rare genetic form of diabetes that is different to type 1 and type 2 diabetes), genetic testing for changes in two genes (HNF1A and HNF4A) should be considered, because these conditions can cause HI in the newborn period that may mimic some forms of acquired HI.

In children who develop HI after 2 years of age, the possibility of an insulinoma should be considered. Insulinomas are usually solitary and benign (not cancer) tumors, but rarely there can be multiple tumors and in some cases the tumor(s) can be malignant (cancer). Insulinomas can be part of a condition called multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1), and genetic testing for insulinomas should include the genes that are known to cause this condition.

Genetically inherited Hyperinsulinism

Genetic forms of HI result from changes in a person’s DNA. DNA is an instruction manual for the body, which is stored within every cell. These changes in the DNA are referred to as genetic variants.

Genetic variants that affect specific parts of the DNA (called genes) providing instructions for the pancreas to produce insulin can cause HI. Sometimes variants can affect genes that provide instructions to more than one part of the body, causing syndromic HI.

Some genetic forms of HI may not be detected until later in life.

Non-syndromic genetic HI (genetic HI which is not associated with a syndrome) is estimated to occur in approximately 1:25,000 to 1:45,000 newborns.

The most common causes of non-syndromic genetic HI are variants in two genes: ABCC8 and KCNJ11. These genes provide instructions to make a channel in the cells of the pancreas. This channel (called the KATP or ATP-sensitive potassium channel) is essential for controlling the amount of insulin released into the body from the pancreas.

Recently, genetic variants in a gene called HK1 have been shown to be an important cause of non-syndromic HI. These variants disrupt a switch in the pancreas which turns ‘on’ and ‘off’ a protein called hexokinase 1. This protein has an important role in breaking down glucose and causing insulin release from the pancreas into the blood.

Over 30 different genetic forms of HI have been reported (see figure below with list). In some cases, the way a child presents with HI may help clinicians to predict which gene is most likely to be disrupted. For example:

- Glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) HI, which results when there is a variant in the GLUD1 gene, is associated with significantly raised levels of ammonia in the blood.

- Short-chain hydroxy acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCHAD) HI, which results from variants in the HADH gene can be associated with a specific pattern on special tests of the blood and urine (high levels of C4-OH acyl carnitine in the blood and high 3-OH-glutarate levels in the urine).

- Hypoglycemia after eating protein is typically seen in individuals with GDH-HI, SCHAD-HI, and KATP channel HI caused by variants in the GLUD1, HADH or ABCC8/KCNJ11 genes respectively.

- High intensity exercise can cause hypoglycemia in some patients with variants affecting a specific part of the SLC16A1 gene.

- Usually, people with HI have low levels of ketones in their blood when their blood glucose levels are low because of excess insulin. This is known as hypoketotic hypoglycemia. For people who have HI because of a variant in the GCK gene, normal or high levels of ketones may be detected when blood glucose level is low after fasting. This is known as ketotic hypoglycemia.

The known genetic causes of hyperinsulinism include:

For more information on the genetic causes of hyperinsulinism, visit CHI’s genetics page.

For most people with HI, the genetic variant causing HI is present in the DNA in every cell of the body. In some children the genetic variant is only present in the DNA stored in the cells of the pancreas. When this happens, the pancreas may have a specific appearance, known as localized islet nuclear enlargement (LINE). LINE HI is sometimes also called mosaic, or atypical HI. Many children with this form of HI will be diagnosed at a later age.

Other ways of classifying HI

Response to Diazoxide

The way that a child’s body responds to treatment with diazoxide may be a useful way of grouping types of HI.

Diazoxide is the treatment that is tried first to manage hypoglycemia in children with HI. A child is said to respond to diazoxide if the key features of hyperinsulinism – hypoglycemia with low ketones – are reversed during treatment.

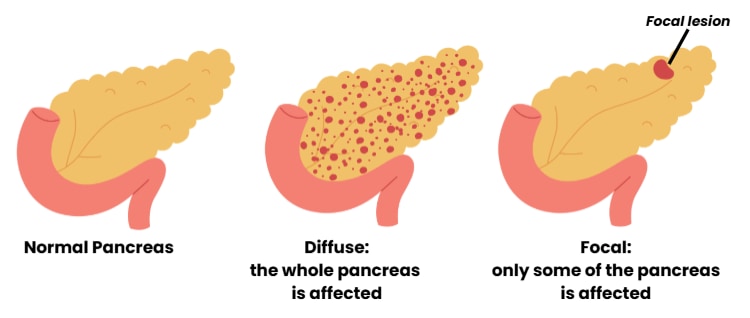

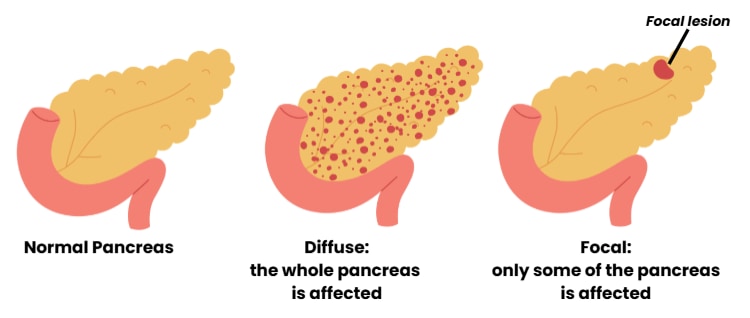

Up to 90% of the children who do not respond to diazoxide have changes in their DNA that disrupt the ABCC8 or KCNJ11 genes. These genes provide instructions for the KATP channel in the pancreas. Many different changes in the ABCC8 and KCNJ11 genes have been found in children with HI. Understanding which specific variants are present and determining whether they are also in the mother’s DNA or father’s DNA can tell us if the child has diffuse or focal HI. In diffuse HI, the whole pancreas is affected. In focal HI, only a limited region of the pancreas is affected.

How can genetics guide clinicians treating HI?

Knowing the genetic profile of someone with HI and their parents may help lead clinicians to proper treatments faster. In some cases, having genetic testing results can predict the HI subtype—meaning genetics can sometimes tell you whether there is a defect in all of (diffuse) or part of (focal) the pancreas. Genetic testing can also be helpful for predicting treatment outcomes. Through genetic research, scientists and clinicians now know that some genetic variants do not respond to diazoxide. In other cases, genetic testing can predict focal HI (which is curable in most cases) with high accuracy. Sometimes, the genetic information in the blood may be different than in the pancreas or other organs and can help guide the treatment plans as well. Often, the most accurate predictions come from knowing the genetics of both the child with HI and their parents, when available. To learn more about HI genetics, please visit https://congenitalhi.org/congenital-hyperinsulinism-hi-genetics/.

There is more likely a genetic cause for HI in children who do not respond to diazoxide. However, in some countries in the world, diazoxide may not be available and sometimes the person with HI cannot tolerate diazoxide –they may have problems with side effects. In such cases the decision to undertake genetic testing should be made by thinking about the individual case.

Genetic testing is recommended whenever acquired HI is unlikely. This includes children who do not respond to diazoxide as well as those who have diazoxide-responsive HI which continues beyond the first 3 months of life.

- Rapid testing of the ABCC8 and KCNJ11 genes is very important for the management of children with diazoxide-unresponsive HI. Rapid testing means that the test is done as soon as the child with HI does not respond to diazoxide and that it is sent to a laboratory which can report the result back within 1–2 weeks. This is important because through finding a single (recessive) variant in ABCC8 or KCNJ11 which has been inherited from the father (who does not have HI) we can identify 97% of the children who have focal HI (where only a part of the pancreas makes too much insulin). Imaging scans of the pancreas can be done to find the abnormal part of the pancreas before surgery. Surgery cures focal HI in most cases.

For hospitals/clinics that do not have access to pancreatic imaging scans, the results of rapid genetic testing of the ABCC8 and KCNJ11 genes will tell a doctor whether the child needs to travel to a center where scans and surgery can be carried out. If rapid testing of these genes is not easily available, the treating hospital/clinic should contact one of the international laboratories which can provide genetic testing, sometimes at reduced cost or without payment on compassionate grounds.

- When no variant in the ABCC8 or KCNJ11 gene is found on rapid testing or when the child still has symptoms of HI after 3 months of age, genetic testing of all other known HI genes should be performed, even if the child responds to diazoxide.

1.5 We recommend that all babies with HI who do not respond to diazoxide should have special scans, called pancreatic imaging studies (e.g., 18 F-DOPA PET scan) to look for a focal lesion that could be surgically removed. Babies whose genetic results confirm they have a diffuse form of HI do not need a scan of the pancreas.

Finding a single recessive genetic variant in the ABCC8 or KCNJ11 gene makes it 97% likely that a child with HI has focal disease. These children should have an 18F-DOPA PET scan of the pancreas. The scan is also recommended for those who have diazoxide-unresponsive HI when genetic testing has not detected any genetic variants, or the results are not clear. 18F-DOPA PET scans may help to find the lesion in focal HI in 75–100% of cases, and this accuracy depends on the experience of the person who reads the results. Very small lesions may not be detected by an 18F-DOPA PET scan, which means that a negative study result does not rule out focal HI.

For children who have been confirmed to have diffuse HI by genetic testing, there is no need for 18F-DOPA PET scan.

Diffuse HI is confirmed when the testing detects a genetic change known to cause diffuse HI.

Recently, a new type of PET scan (68Gallium NOGADA exendin 4 PET/CT) has been examined for use in imaging the pancreas to help detect lesions. Further evaluations need to take place before this can be recommended for use in HI. Scans of the pancreas using other techniques such as ultrasound, computerized tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are not helpful in detecting focal lesions in children with HI and should only be used in older children who might have an insulinoma.

2. Medical Management

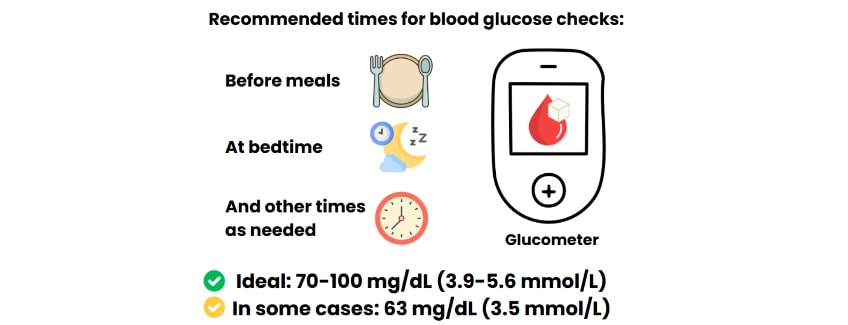

2.1 We recommend that the goal of treatment for hyperinsulinism is to keep blood glucose

levels within the normal range of 70-100 mg/dL (3.9-5.6 mmol/L).

The Pediatric Endocrine Society (PES) guidelines say that blood glucose levels should be kept above 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) to prevent hypoglycemia unawareness (when a person cannot sense that they are having an episode of hypoglycemia) and to have a safe margin above the level of hypoglycemia that causes brain damage. Once the blood glucose levels are stable, the next step is to identify the best treatment plan according to the type of HI.

Despite efforts to maintain blood glucose levels within the normal range (70-100 mg/dL, 3.9-5.6 mmol/L), children with severe forms of HI may drop below this threshold. For these children with severe HI, a lower hypoglycemia threshold of 63 mg/dL (3.5 mmol/L) may be accepted, depending on how often they have episodes of hypoglycemia, and if it is possible to change the treatment.

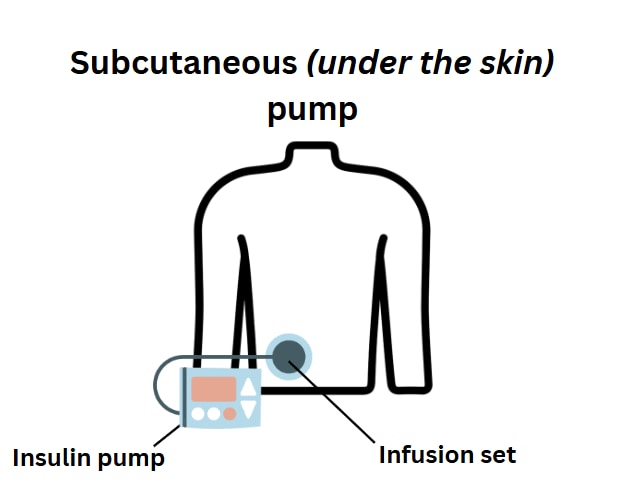

Blood glucose checks by glucometer testing should be done as often as the individual needs. Usually testing is done before meals and at bedtime, with extra tests when needed. Currently, there is not enough evidence to recommend continuous glucose monitoring by subcutaneous (under the skin) continuous glucose monitoring sensors (CGMs).

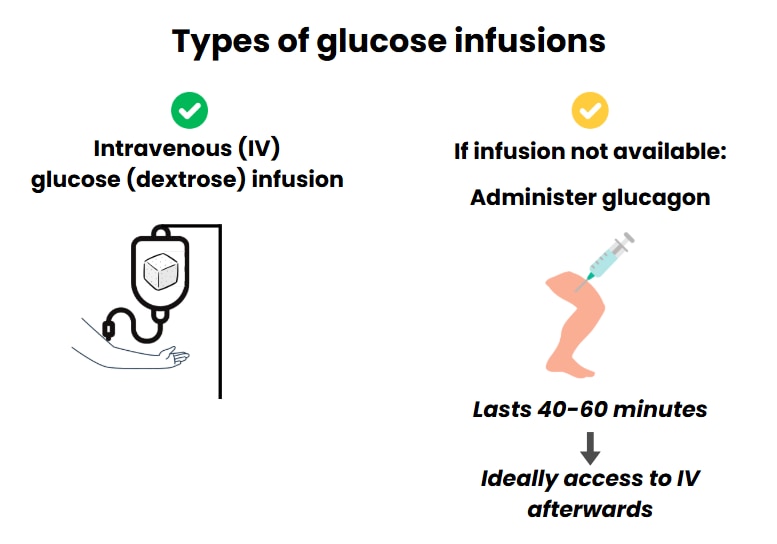

2.2 or newborns with hyperinsulinism we recommend starting the treatment of hypoglycemia by using intravenous (IV) glucose (dextrose) infusion to bring blood glucose levels into the normal range.

Intravenous glucose (dextrose) should be used without delay to correct hypoglycemia and bring blood glucose levels to the normal range. The usual dose is a bolus (quick infusion) of 200 mg/kg (2 mL/kg of 10% dextrose solution) followed by continuous infusion of dextrose at a rate that is high enough to keep blood glucose levels above 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/dL). This usually means an intravenous infusion rate of at least 8 mg/kg/min.

When a child is known to have HI and has an episode of hypoglycemia and IV therapy is not immediately available (for example, no IV line in place), glucagon (with doses of 0.5-1 mg or 20-30 mcg/kg) can be used. Glucagon is given as an injection either into the muscle (intramuscularly) or under the skin (subcutaneously). The effect lasts up to 40 – 60 mins, allowing time to insert an IV line.

Some babies with HI need intravenous glucose rates as high as 20-30 mg/kg/min, and rapid increases in the glucose infusion rate may be needed. In these babies, who are clearly using up large amounts of glucose, we suggest rapidly increasing glucose infusion rates by increments of 4 mg/kg/min or greater, taking care not to cause fluid overload (too much fluid in the body).

Following a 200 mg/kg dextrose bolus and an infusion of 8 mg/kg/min dextrose, steady blood glucose levels are reached in 10 minutes. Blood glucose testing is then repeated to avoid giving too much glucose. Some babies need a central venous catheter (Central Line or PICC line) to give dextrose solutions in high concentration (it can be diluted in less fluid if it goes into a large central vein – giving large amounts of fluid can cause additional problems for some babies).

2.3 We recommend continuous intravenous infusion of glucagon for children who have a risk of fluid overload because of a high glucose requirement.

Because glucose is mixed with water to make an intravenous infusion, a high rate of glucose infusion may mean that the body is given more water than it needs, leading to ‘fluid overload’. Fluid overload can put strain on the heart, lungs and kidneys. When a high dose of intravenous glucose is needed, a continuous intravenous infusion of glucagon can be given alongside. This will help control hypoglycemia and prevent complications from fluid overload by reducing the rate of intravenous dextrose infusion needed, and therefore the amount of fluid given.

An intravenous infusion of glucagon (dose range 2.5-20 mcg/kg/hour) can help maintain normal blood glucose levels in HI. Glucagon makes the liver release stored glucose into the blood.

Side effects of glucagon infusion may include vomiting (13%), rash (2%), and breathing difficulties (19%). A rare but important side effect of glucagon is a skin problem called necrolytic migratory erythema skin rash (NME). Some patients have been tried with long-term continuous infusion of glucagon under the skin by pump, but at the moment, this is unreliable because fibrils and crystals can form and block infusion lines.

2.4 Diazoxide

2.4 We recommend diazoxide as the first-line treatment for patients who have been diagnosed with hyperinsulinism.

Diazoxide is part of a group of medicines called benzothiadiazides. It is related to thiazide diuretics that were initially developed for treatment of high blood pressure, but later found to be useful to treat HI due to the way it slows down insulin release. Diazoxide slows down insulin release by opening the KATP channels in cells in the pancreas called beta-cells. Diazoxide can be available in a pill form or a liquid form; however, not every country has both forms available.

In 1976, diazoxide was approved in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for HI in children.

The dose range of diazoxide in babies and children with HI is 5 to 15 mg/kg/day by mouth. Higher doses offer no additional benefits but worse side effects. In adults, a dose range of 3-8 mg/kg/day is recommended.

The half-life of a drug is the time it takes for the drug’s active ingredient to reduce by half. The half-life is used to decide how long a dose will last effectively, and how often the drug should be given. The half-life of diazoxide in children was recently estimated to be 15 hours, varying between 10.3 -20.3 hours; this means diazoxide may be given two or three times a day.

Diazoxide can cause fluid retention, particularly in newborns. To avoid fluid retention, a diuretic (a medication that helps the body get rid of fluid) should be started at the same as starting diazoxide. Diuretic doses of chlorothiazide of 10mg/kg/day or hydrochlorothiazide of 1-2 mg/kg/day may be used particularly when giving higher doses of diazoxide, such as 10mg/kg/day.

Diazoxide is said to be working if the key features of hyperinsulinism – hypoglycemia with low ketones – have been reversed.

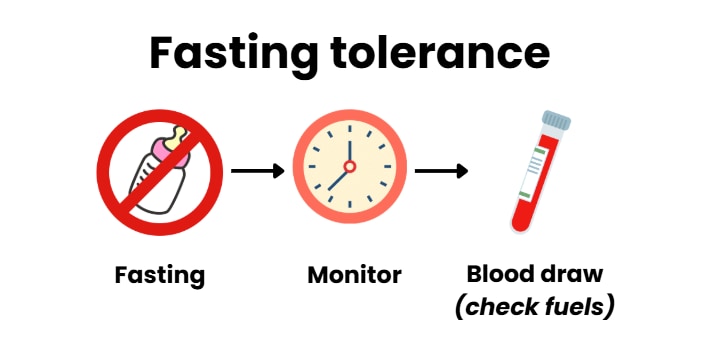

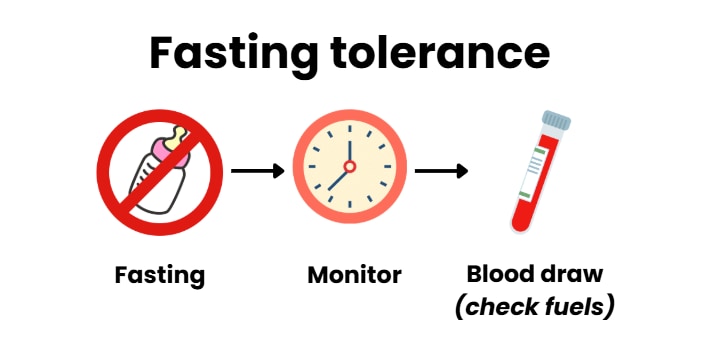

This means showing that the child can fast (go without feeding) and generate high ketone levels (hyperketonemia, BOHB levels >1.8 mmol/L) before they develop hypoglycemia (glucose levels below 50-60mg/dl, or 2.8-3.3 mmol/l).

If the rate of dextrose infusion cannot be reduced after 5 days of treatment with diazoxide at a dose of 15 mg/kg/day or if HI has been confirmed to be diazoxide-unresponsive (diazoxide is not working well enough) by a fasting test, diazoxide should be stopped.

If the child does not respond to diazoxide, this suggests a problem with the KATP channel caused by a variant in the ABCC8 or KCNJ11 genes. Other genetic forms of HI may also be diazoxide-unresponsive, such as glucokinase (GCK) HI and hexokinase (HK1) HI.

The side effects of starting diazoxide include:

- Salt and water retention which may lead to fluid overload

- Edema (swelling caused by fluid retention)

- Hyponatremia (low salt levels in the blood)

- Tachypnoea (fast breathing), and respiratory failure (breathing difficulties)

- Pulmonary hypertension (changes in pressure in the blood vessels between the heart and lungs) has been found in 2.4% of the babies in a large study group

The long-term side effects of diazoxide include:

- Hypertrichosis (excess hair growth) is the most common; recently reported in 84.1% of children.

- Coarsening of facial features has been reported in 24% of children

- Neutropenia (reduced number of white blood cells which are used to help fight infection) in 15.6% of children

- Thrombocytopenia (low platelet count – platelets help blood to clot) in 4.7% of children

- Hyperuricemia (increased levels of uric acid in the blood) in 5.0% of children (uric acid is a normal body waste product, formed when chemicals break down)

The impact of the neutropenia is not known, and we do not know the level of neutropenia that should make us stop giving a child diazoxide. A blood test can be checked before starting diazoxide to look for any pre-existing neutropenia or thrombocytopenia.

An estimated 9.7% of people who start diazoxide treatment cannot continue to use it due to severe side effects. The rate of side effects appears to be higher in children treated for perinatal stress induced HI (PSHI) and in premature babies.

For all these reasons, it is recommended to screen for the side effects of diazoxide, including an echocardiogram (heart scan with ultrasound) one week after starting on diazoxide treatment, and screening for symptoms of pulmonary hypertension. A complete blood count, including measurement of all white blood cell types (differential) and serum uric acid levels should be checked every 6 months.

There have been no studies published about the impact of high uric acid levels when taking diazoxide. More general studies have shown that long-lasting hyperuricemia (high levels of uric acid) in children can lead to monosodium urate deposits that may progress to gout, just as in adults. This means it is important to screen for hyperuricemia in children treated with diazoxide.

2.5 Somatostatin Analogues

Somatostatin analogues (SSAs) are drugs that slow down the production of hormones (insulin is a hormone).

We suggest the use of somatostatin analogues as the second choice of treatment for children with hyperinsulinism who are diazoxide-unresponsive, or have unacceptable diazoxide side effects, or are unable to obtain diazoxide.

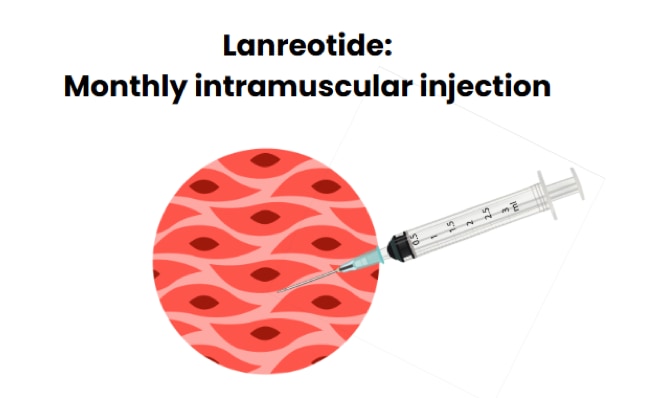

Short- or long-acting somatostatin analogues used in people with HI include octreotide, long-acting octreotide (octreotide LAR), and lanreotide.

Octreotide has been used since the late 1980s as a long-term treatment for HI to avoid the need for pancreatectomy (surgery to remove the pancreas) or in cases that could not be controlled following pancreatectomy. However, the use of octreotide is limited because it becomes less effective over time (tachyphylaxis) and can have important side effects, including necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC – a serious bowel problem), particularly in premature and high-risk babies with unstable or low blood pressure or sepsis (serious infection).

While somatostatin analogues are commonly used as the second choice of treatment for HI, they have not been approved for this use by a regulatory body. (Even though these medications are not officially approved for people with HI, they are still frequently used and are considered safe.)

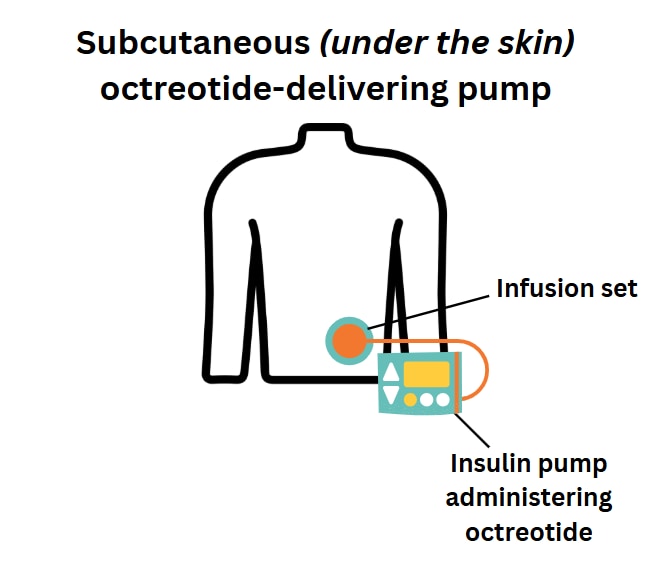

Octreotide can be given in 2-4 subcutaneous doses (injection under the skin) per day or by continuous subcutaneous infusion (an infusion that goes just under the skin) using commercial pumps intended for insulin administration. The starting dose of octreotide is 5-10 mcg/kg/day, and it can be increased up to a maximum of 20 mcg/kg/day.

To try to prevent the development of tachyphylaxis (the body becoming used to octreotide, so that it works less well), some centers use two doses of octreotide during the daytime, alongside continuous overnight dextrose administered through a gastrostomy tube (tube inserted through the belly that brings nutrition directly to the stomach).

A single monthly injection of a long-acting somatostatin analogue (SSA: octreotide LAR or lanreotide) can be easier to manage than multiple daily octreotide injections or continuous subcutaneous octreotide by a pump. With a pump there is a risk the pump could become disconnected or break down.

The dose of long-acting SSA that is needed to control hypoglycemia varies, and that is why there is not enough data available to make a recommendation of the dose. For octreotide LAR, the experts suggest calculating the total monthly dose of octreotide and giving it as a single dose of octreotide LAR once per month. For lanreotide, 30-60 mg once a month is a typical starting dose.

Screening for side effects while on SSA therapy is recommended, including growth monitoring, a gall bladder ultrasound scan to look for gallstones (cholelithiasis), and blood tests for liver enzymes, growth factors, and thyroid function at least every 6 months.

2.6 Other Drug Treatments

We suggest that medications which lack adequate proof (such as nifedipine, sirolimus, etc.) are not used to treat hyperinsulinism unless part of an approved research trial.

There are some other drug treatments that do not have enough proof that they work well for HI.

Tests in the research laboratory showed that calcium channel blockers can slow down insulin production and suggested that the calcium channel blocker nifedipine could be beneficial for HI, but most major centers have not found it useful and do not recommend its use.

The exception is that for patients with HI caused by variants in the CACNA1D gene, which provides the instructions for a calcium channel in the pancreas, it has been suggested that nifedipine may improve not only hypoglycemia, but also neuromuscular difficulties which are associated with this subtype of HI.

Sirolimus is a drug which can be used to decrease the activity of the immune system, for example after a transplant. Sirolimus has been used in some children with HI who do not respond to any medical treatments, based on reports of it helping adults with insulinoma. However, due to serious concerns over the risk of life-threatening infections, hepatitis, diabetes mellitus, and pancreatic insufficiency, and the absence of proof of its effectiveness, the Guideline Committee cannot recommend sirolimus for routine clinical use in HI. Exceptions should only be made for studies of the drug carried out under approved research trials.

Glucocorticoids have been used in the past to try and increase glucose levels by inducing insulin resistance (changing the way the body responds to insulin); however we suggest that they are not effective in treatment of HI and should be avoided since the risks strongly outweigh any benefits.

2.7 We suggest carbohydrate supplements to maintain normal blood glucose in children with hyperinsulinism who are not adequately controlled on medication alone.

Many children with HI continue to have unstable hypoglycemia and need continuous intravenous treatment with glucose, despite receiving the maximum amount medication that is safe or having surgery.

For these children, continuous feeds of a solution with glucose (dextrose or maltodextrin polymer powder) at concentrations up to 20% may be used, either via nasogastric tube or, preferably, via gastrostomy using portable pumps.

In some cases, adding glucose to formula feeds to increase the total carbohydrate content to 15% may be helpful; however, care should be taken to avoid interfering with appetite and normal feeding behavior or causing obesity due to the excess calories.

Some reports have suggested that drinks containing uncooked cornstarch may help older children and adults with HI who have unstable control of hypoglycemia to go longer without eating (for example at night). Doses of 1-2 g/kg may be used, but only in children over 9 months old because cornstarch is poorly digested in younger babies. As there has been no formal research into the benefits of cornstarch in HI, the Guideline Committee was unable to provide a recommendation on its use.

3. Surgical Management

3.1 We recommend that surgery be considered for children who are suspected to have a focal lesion that can be removed.

3.2 We suggest that children with hyperinsulinism due to diffuse HI should undergo surgery if hypoglycemia cannot be controlled with medical treatment..

When genetic tests and special scans of the pancreas suggest that a focal lesion is likely, surgery to remove this lesion from the pancreas is the treatment of choice. This is because these children can be cured and avoid ongoing hypoglycemia and development of diabetes mellitus (diabetes mellitus occurs when a lot of the pancreas is removed, but not when only a small portion of the pancreas is removed). This is especially true if the position of the lesion makes it easy to remove entirely and if the surgical team has the necessary expertise.

There should be a protocol for sending samples of pancreatic tissue to be checked in the laboratory while surgery is happening, to make sure that the entire lesion is removed (intra-operative frozen biopsy). This helps the surgeon decide the best approach; for example, in some cases, removal of lesions in the pancreatic head may require a procedure called Roux-en-Y pancreatojejunostomy that keeps pancreatic duct connections from the body and tail of the pancreas.

During surgery for suspected focal HI, biopsies should be taken from the head, body, and tail of the pancreas to clearly establish whether there is diffuse disease or an underlying focal lesion.

Diffuse HI can be recognized by nucleomegaly (increased numbers of islet cells with a large center, or nucleus) throughout the pancreas; the laboratory test on these is ideally undertaken by a pathologist (laboratory doctor) experienced in recognizing HI.

Focal lesions are usually small, 0.5-1 cm in diameter. They contain high numbers of endocrine cells (cells that produce hormones) often with some acinar cells (cells that make enzymes) and duct structures; biopsies from the remaining pancreas are usually normal. Focal HI lesions often have unclear edges and extend into the nearby normal pancreatic tissue, making it challenging to assess how and where to remove tissue. In Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome (a genetic syndrome that includes HI), the increase in endocrine tissue is seen over large areas of the pancreas. This can make complete removal of this tissue difficult.

Sometimes the cell changes that are typical for diffuse HI occur only in some cells of the pancreas (instead of the whole pancreas); this is called LINE-HI or mosaic, or “atypical” HI. These genetic changes are called somatic variants and have been found in the ABCC8, GCK, and HK1 genes.

Due to the variety of histologic forms (how the cells look under a microscope) of HI, the choice and plan for pancreatic surgery should be made working with a pathologist (laboratory doctor) experienced in HI and with access to a high-quality laboratory and suitable protocols for rapid and accurate review of pancreatic biopsies.

When diffuse HI has been diagnosed by genetic testing, medical treatment is the first choice; however, if hypoglycemia cannot be adequately controlled, the pancreas may need to be surgically removed (pancreatectomy).

For diffuse HI, it is recommended to remove 90-98% of the pancreas to aim to control hypoglycemia but also try to delay the development of diabetes (by leaving a small part of pancreas) and preserve bile duct drainage. The removed pancreatic tissue should be examined in the laboratory (immunohistochemical staining) to find out more about the child’s HI.

After surgery, children with HI should be cared for in an intensive care setting.

Blood glucose levels can change quickly during and just after surgery. It takes time after recovery from surgery to know if the surgery has worked to improve HI. Prevention of post-operative hypoglycemia during this period is important to reduce the risk of a shortage of glucose to the brain. Blood glucose levels should be monitored closely, with a goal of preventing hypo or hyperglycemia (high blood glucose).

After surgery, if the child continues to have hyperglycemia (>250 mg/dL) that does not respond to intravenous fluids, or if there are high blood glucose levels with high ketone levels (beta-hydroxybutyrate levels >2 mmol/L.), insulin should be started either by subcutaneous injection or by infusion. The need for insulin may be temporary.

If the child still needs insulin when they are ready to start feeding again, insulin administration can be changed to the subcutaneous route (under the skin).

Babies and children who have hypoglycemia after surgery and cannot be weaned from intravenous glucose infusions may require further medical management for persisting HI.

The outcome following pancreatectomy depends mainly on the type of HI the child has.

Following pancreatectomy, regardless of the type of HI, children may:

- have blood sugars in the normal range needing no further treatment

- still have persistent hypoglycemia requiring medication or nutritional support

- have hyperglycemia requiring insulin treatment (diabetes)

Once they are stable post-surgery, babies and children need to be assessed to determine if they will need treatment for blood glucose levels.

Children who are weaned from IV glucose without hypoglycemia should have a fasting study (not eat for a period of time) to demonstrate whether they are cured or need further medical management.

A cure of HI can be demonstrated by the child developing high ketone levels (hyperketonemia or beta-hydroxybutyrate >1.8 mmol/L) before their blood glucose levels drop to < 50 mg/dL (2.8 mmol/L)].

Further surgery to remove more pancreatic tissue may be needed if the hypoglycemia cannot be controlled.

Some studies have reported that in over 95% of cases when surgery is performed for focal HI, it has cured the child. The risk of developing diabetes after surgery is low when just the focal lesion is removed.

After most of the pancreas is removed (95-98% or subtotal pancreatectomy) for diffuse disease, about half of children will still have hypoglycemia (50-60% of children). In these situations, after the surgery, additional medical treatments are sometimes enough to control blood glucose, but some babies may need a second surgery on their pancreas. Approximately 25% of children who have had most of their pancreas removed (near-total pancreatectomy) develop permanent diabetes relatively soon after the surgery. The number of children who develop diabetes after pancreatectomy increases with age -this number can rise to 91% by 14 years of age.

Children who have undergone greater than 50% pancreatectomy or a procedure called pancreatojejunostomy may not be able to produce enough pancreatic enzymes to digest the fat in their food and may need pancreatic enzyme replacement.

A fecal elastase assay (a lab test on a stool sample to measure one of the “digestive juices” that the pancreas makes to help digest food) is commonly used to check for this. Other recommended monitoring includes blood levels of fat-soluble vitamins (vitamins A, D, and E) and coagulation tests (blood tests) for vitamin K deficiency.

4. Discharge Planning

4.1 We suggest that discharge planning for children with hyperinsulinism includes an assessment of fasting tolerance.

Before discharge from the hospital, a fasting study (how long a person can go with eating before blood glucose drops) to determine the control of HI is suggested for all children regardless of whether they are on medical therapy or have undergone pancreatic surgery. The length of the fast should be decided for each person to ensure that they will be safe in their home environment and to guide the child’s sleeping, feeding, and glucose monitoring regimen.

For children with ongoing hypoglycemia, we suggest gastrostomy tube placement prior to discharge home for use in emergency situations or for continuous overnight feeds/dextrose when fasting tolerance is too short for safe overnight glucose control. Safety plans should be considered for accidental disconnection of overnight continuous feeds; these may include the use of a continuous glucose monitoring system and nocturnal enuresis alarm pad (designed for bed wetting but used here to identify if the feeding set is leaking).

Individuals who still have episodes of hypoglycemia should also have access to glucagon therapy for use in an emergency.

An individualized approach should be taken for decision-making regarding child and family readiness for safe discharge home. Upon discharge, any required medications, supplies for glucose monitoring, discharge summary letter/ emergency management plans for hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia, and follow-up plans should be provided to the family both in their own language and the primary language of the country where they live.

Other medical and psychological problems should also be addressed before discharge.

In a recent study, caregivers reported that the on-going worry associated with managing the complexity of their child’s HI can impact their physical and mental health. Therefore, we suggest providing psychological resources to families and offering them connections to HI patient organizations for support. Referral for genetics consultation and counselling may also be indicated.

5. Long-Term Management of Patients with Hyperinsulinism

5.1 We suggest regular follow-up and monitoring to assess blood glucose control, medication side effects, and the development of diabetes or pancreatic insufficiency.

All children with HI need regular monitoring of their blood glucose levels at home to guide treatment adjustments.

More than 65.2% of people with HI need adjustments to the treatment plan in the first three months following discharge and despite careful follow-up, episodes of hypoglycemia are common.

The side effects of the HI medications should be monitored, and support should be provided from the multidisciplinary feeding team in the hospital as well as in the community.

In some children with certain forms of HI (e.g., HI caused by variants in the ABCC8, KCNJ11, HNF1A, or HNF4Agenes), HI may become less severe over time allowing dose adjustments to medications.

For children who have undergone a subtotal pancreatectomy (almost all of the pancreas has been surgically removed) and are no longer on treatment for hypoglycemia, screening for diabetes should include hemoglobin A1c (blood test) every 6-12 months and monitoring for symptoms of hyperglycemia (high blood glucose).

Transition to diabetes may be slow and some patients may have both hypoglycemia after fasting and hyperglycemia after eating. The need for diabetes medications should be evaluated on an individual basis considering the current HbA1c (blood test to look for a pattern of high blood glucose), ability to fast without hypoglycemia and presence or absence of symptoms of diabetes.

In people with HI who develop diabetes mellitus following surgery, insulin treatment by conventional or pump therapy, like children with type 1 diabetes mellitus, is necessary to achieve control of blood glucose.

Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy should be started when there is evidence of pancreatic insufficiency. Pancreatic insufficiency is a condition where the pancreas does not make enough of the enzymes needed to break down food. This can cause symptoms of greasy stools and a risk for health and growth problems if the body cannot store and use certain vitamins and nutrients.

5.2 We recommend that, due to the increased risk of developmental difficulties and feeding problems, all children with hyperinsulinism should be referred for developmental follow-up, feeding assessment, and early intervention.

Neurodevelopment delays and neurological disorders, including epilepsy and microcephaly (slow brain growth), due to hypoglycemic brain injury occur frequently in people with HI.

Infantile spasms (a type of seizure); motor and speech delay during early childhood; or difficulties with attention, memory, visual, and sensory and motor functions have also been reported.

Children with transient HI are also at risk of developing neurodevelopmental difficulties with 26 to 44% of them having changes in neurodevelopment.

Changes in neurodevelopment and seizures are particularly common in GLUD1 HI.

Children with HI should have regular neurodevelopmental follow-up and monitoring.

This should include formal neurodevelopmental testing during early childhood to assess appropriate schooling and support. The care of children with HI may need to involve neurodevelopmental pediatricians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and speech and language therapists.

Feeding problems may be associated with HI and can be complex and have multiple causes. Feeding issues have been reported in 68.6% of all HI patients. Vomiting, sucking and swallowing difficulties, and not wanting to eat can occur as a single issue or in combination. Babies with HI can be at risk of problems with feeding or interruption with normal feeding milestones because of unpleasant tasting medications that cause nausea and loss of appetite; the use of intravenous glucose support; and tube feedings with high carbohydrate content that impair appetite.

Although preventing hypoglycemia is the primary goal, we suggest encouraging oral feeding over tube feeding especially when intravenous glucose support is being used to control hypoglycemia.

Prompt management of medical problems, such as vomiting and gastroesophageal reflux (acid from the stomach in the esophagus), may help to prevent long-term feeding problems. In addition, in children with ongoing hypoglycemia, insertion of a gastrostomy tube should be considered for prompt correction of hypoglycemia and parents should be advised of the possibility of tube dependency and how to avoid this complication.

5.3 We suggest that programs are established for the transition to adult care for children and adolescents with hyperinsulinism and ongoing medical needs, and for the development of adult programs for adults with hyperinsulinism.

Adults with HI who continue to have complex needs require transition of care to appropriately trained adult specialists to address all ongoing issues, including HI treatment, neurodevelopmental delays and memory issues, hypoglycemia unawareness, risk of developing diabetes after pancreatectomy, and the meaning of having a genetic diagnosis.

Conclusions

Scientific and clinical advances over the last three decades have improved our understanding of HI in children and have led to treatment approaches that consider the many differences in their genetic results.

Despite these advances, treatment options are still limited for most children with HI.

Children living with HI continue to experience high rates of neurological difficulties due to hypoglycemia-induced brain damage.

To improve neurological outcomes, prompt recognition of hypoglycemia and its causes leading to rapid and effective treatment are essential.

Currently, pancreatectomy may be required for the surgical treatment of diffuse HI. New medical therapies are urgently needed to prevent the need for pancreatectomy because it is not sufficient to prevent hypoglycemia and diabetes that can occur after surgery. In addition, new medical treatment choices are needed to replace the current medications that may cause significant side effects.

Centers caring for babies and children with HI should consider developing multidisciplinary teams to provide all aspects of care, including social and psychological support for the children and the families.

An individualized approach to each child ensures the best patient experience and outcomes. It is also important to offer long-term peer support to patients and families.

There are a host of national and international family support organizations that can be found online. congenitalhi.org/links/

These guidelines provide a systematic approach to the diagnosis and management of children with persistent hypoglycemia due to HI while at the same time recognizing that access to diagnostic tools, medications, and medical and surgical expertise is limited in many areas of the world and good quality evidence is often lacking. This shows the urgent need for collaborative research efforts to generate this evidence.

Glossary of medical terms

Beta-cell – cells in the pancreas that make and release insulin

Blood glucose/sugar – the level of glucose (sugar) in the blood

Central venous catheter – a large cannula that is threaded into a big vein in the body

Congenital – something you are born with

Continuous glucose monitor – a device that sticks to the skin and measures glucose levels. A tiny plastic tube goes through the skin to measure the glucose levels in the fluid just below, sending data to a small monitor or phone app.

Diazoxide responsive – someone whose HI can be successfully treated with diazoxide

Diffuse HI –a type of HI indicated by abnormal beta-cells throughout the pancreas

Dominant HI –genetic HI caused by one variant; this means that a person has a genetic change in one copy of that gene, not both copies. The person may have inherited this variant from a parent (who can also have symptoms or may not have symptoms, because dominant HI may not occur in every person who has the variant) or the variant may have arisen as a new (de novo) non-inherited genetic change in this individual.

Endocrinologist – a doctor who specializes in problems with hormones (like insulin)

Fluid overload – too much fluid in the body

Focal HI – a type of HI where abnormal beta-cells are limited to a particular region in the pancreas (a focal lesion)

Gene – genes include the code which gives instructions to how all the parts of our body should be built and function. Normally we have two copies of each gene, one inherited from the mother and the other from the father. Changes in genes (variants) can cause disease.

Genetics – the study of genes and how traits are passed from one generation to the next

Glucagon – a hormone that helps to raise the blood glucose levels

Glucometer – a handheld device that uses a small drop of blood to test blood glucose levels

Hormone – a substance that is made and secreted from one part of the body and performs its job in another part of the body

Hyperinsulinism (HI) – a health condition that means you have too much insulin in your body

Hypoglycemia– low blood glucose

Hyperglycemia – high blood glucose

Hypertrichosis – more hair than usual, on the head and body

Insulin – a hormone made by the body. Insulin is needed to help get fuel into all the cells in the body. Insulin works to lower blood glucose levels.

Islet cell – a cluster of cells in the pancreas including the beta-cells where insulin is made

Intramuscular (IM) – an injection into the muscle

Intravenous (IV) – into a vein

KATP channel – part of the beta cell in the pancreas that controls insulin release

Ketone – fuel used by the body, a major ketone is called beta-hydroxybutyrate (BOHB)

Ketotic – high levels of ketones in the blood, usually happens when fasting

Pediatric – about babies, children and teenagers

Pancreas – an organ in the belly; one of its jobs is to make insulin

Pancreatojejunostomy – a procedure that may be performed during pancreatectomy surgery to connect the pancreas to the intestine

Pathologist – a doctor who works in the laboratory testing samples and helping to diagnose the cause of illness

PET scan – an imaging technique that allows doctors to visualize focal lesions

Recessive HI – genetic HI caused by two variants; this means that a person has to have changes in both copies of a gene. The person has typically inherited both of these variants from the parents, one from the mother and one from the father. But the parents do not have HI because if someone has only one recessive variant (with a normal copy of the gene) it does not cause HI.

Somatic variant – genetic change has happened during individual´s development so that it may affect a body part or several body parts but cannot be detected from blood sample

Subcutaneous – an injection or infusion that goes into the tissues under the skin

Variant – in genetics, variant refers to a change in a gene that can cause disease